Beth-El’s design remains a fine example of Modernism

When dedicated 60 years ago, Temple Beth-El was one of the first examples of modern synagogue architecture in New England. Lovingly preserved, it remains one of the finest.

When dedicated 60 years ago, Temple Beth-El was one of the first examples of modern synagogue architecture in New England. Lovingly preserved, it remains one of the finest.

During the early 1940s when planning began for the congregation’s third home, on Orchard Avenue, clergy and lay leaders were unsure whether to seek a traditional or more adventurous design. Rabbi William G. Braude led an extensive search for both an appropriate style and an architect, which, with board approval, culminated in 1947 with the selection of Percival Goodman. A professor of architecture at Columbia University, he had recent synagogue-building experience and was eager for a similar commission (despite the fact that he was never an observant Jew).

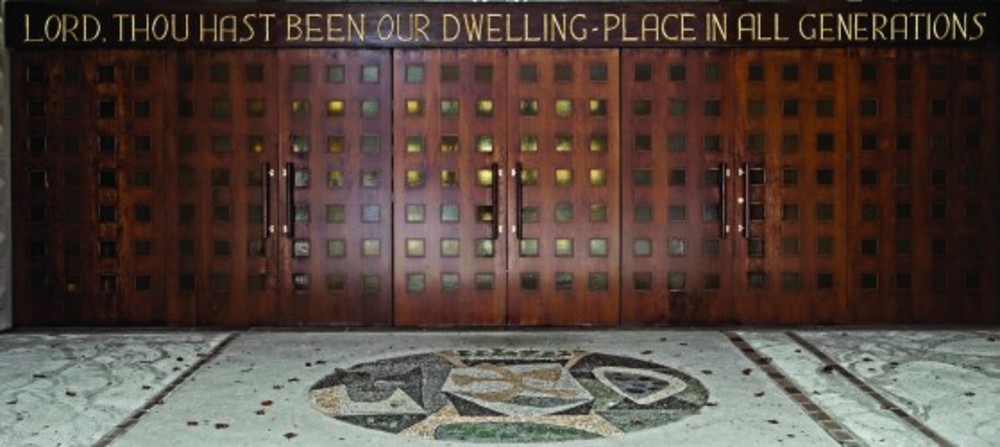

Of course, Goodman and his clients considered the new Beth-El – its entire building and grounds – as a work of art. Low-key and inviting, the design was intended to express tranquility, timelessness and majesty while harmonizing with nature and neighboring buildings. The sanctuary’s clerestory windows, whose calligraphy and symbols were designed by Ismar David, invited a dramatic interplay of bright light, shadow and darkness. Boldly colored textiles and marble memorial panels further enhanced the sanctuary’s contemplative yet joyful aura. Walter Feldman, a Brown University art professor, was commissioned to craft figurative mosaic pavements for the temple’s foyer. Of course, music, the spoken word and silent prayer were also integral to Goodman’s understated aesthetic. As were flowers!

Unfortunately, Goodman’s grandest decorative ideas, being too costly, never materialized. The first consisted of two stone relief carvings by the great Jewish modernist Jacques Lipchitz that would have adorned the temple’s south façade (above the office entrance) and the eastern end of the sanctuary (facing Butler Avenue). Another extraordinary idea was for a pair of tapestry-like curtains, flanking the sanctuary, that would have been designed by another major Jewish modernist, Marc Chagall.

Fortunately, several prominent members of New York’s avant-garde, many associated with the Samuel Kootz Gallery, received commissions. David Hare sculpted the Ner Tamid and a seven-branched candelabra, which mysteriously resembles a nautical vessel. Herbert Ferber sculpted the bronze hanukkiah adjacent to the sanctuary’s front entrance.

Ibram Lassaw, an Egyptian-born Jew also associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement, created the spidery metal columns flanking the ark. Brilliant suggestions by Rabbi Braude, the “Pillar of Cloud” and the “Pillar of Fire” (Exodus 13:21-22) had protected and guided the wandering Israelites. One of Lassaw’s sculptures was actually missing during the temple’s dedication. So highly regarded, it was borrowed by the Museum of Modern Art for exhibition at the Venice Biennale.

I am particularly fond of Lassaw’s columns. When illuminated from below, they convey a sense of everlasting space, time and divinity. Indeed, the recurring letter shin symbolizes Shaddai (The Almighty). I was fortunate to interview Lassaw at his East Hampton studio in 1988 when researching a lengthy article about Beth-El’s art and architecture. Not surprisingly, he was a soft-spoken and humble man.

Remarkably, Goodman’s design did not include sculptures of the Ten Commandments. Indeed, there was no place for them within the latticework of the arched roof. In 1960, when some congregants seemed unhappy with this oversight, Goodman recommended a sculptor, Martin Craig, to fill the so-called gap. Although Goodman thought that it was unnecessary to place Hebrew letters on the chapel’s small ark, he also submitted to some congregants’ objections.

When I interviewed him in 1989 shortly before his death, Goodman explained that he was particularly proud of Providence’s Beth-El. As the designer of more than 50 postwar American synagogues, however, he had no need to flatter my congregation or me. He strongly believed that the Orchard Avenue commission represented a wonderful opportunity: an ample budget and site, thoughtful clients and a fresh opportunity to reinterpret the past. Horrified by the threat of nuclear war, Goodman was also concerned that the pews were seldom filled to capacity. Thus, in a surprising sense, Beth-El’s gentle, graceful and gracious design was also illusory.

GEORGE GOODWIN, a Beth-El member since 1987, was co-editor of “The Jews of Rhode Island” (Brandeis University Press, 2004) and has edited the Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes for a decade.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is part of a series about Hiddur Mitzvah (enhancement or beautification of the divine commandment). In appreciation of Hiddur Mitzvah The Jewish Voice will highlight Judaica collections in our synagogues and museums throughout the state.